“What we’ve got here is a failure to communicate.” — Cool Hand Luke, who could have been discussing the Kidder Massacre

We wear a computer called a telephone, and tend to panic when we lack a signal. We often can’t endure being out of touch. In the 1860s, electronic communication was limited to widely-separated telegraph stations. Because no one at Fort Sedgwick knew George Armstrong Custer‘s full orders, and the army’s other intelligence and communication failures, 14 men died in the Kidder Massacre in Kansas.

Related: Custer died at the Battle of Little Bighorn in Southeast Montana.

Lieutenant Lyman Stockwell Kidder, his Lakota scout Red Bead, and 10 enlisted men, Sergeant Oscar Close, Corporal Charles Haines, Privates Rodger Curry, Michael Connell, William Floyd, Michael Gorman, N.J. Humphries, Michael Haley, and Charles Teltow all died in the Kidder Massacre in July 1867. They took Yellow Horse and another Sioux warrior with them. The battle took place about 20 miles northeast of Goodland, Kansas.

The failures that led up to the Kidder Massacre displayed all the failures of General Winfield Scott Hancock’s 1867 campaign, called Hancock’s War. Civil War officers were used to set-piece battles and go-for-glory cavalry charges. The Sioux and Cheyenne warriors didn’t use those tactics. They were light cavalry who employed guerilla tactics. The US cavalry needed to be far more nimble to stop them.

Ad: Learn more about Hancock’s War.

Kidder’s Civil War experience | Custer lacks orders | Kidder at Fort Sedgwick | Massacre prelude | Lost patrol | Found patrol | The warriors; story | A father’s search | A father’s escort | Recovering the bodies | Burials | A lost identity | Participants die young | Dog Soldiers break | Finding a dinosaur | Buffalo hunters killed | Custer meets Kidder’s fate | Battle site today | Driving directions |

Kidder: An experienced soldier and officer

Kidder had fought in the war, too. When he applied to become a post-Civil War regular officer, he said he had fought in Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee skirmishes during the Civil War.

Ironically, Kidder had more Indian-fighting experience than his commanders. He enlisted into the Union’s Fifth Iowa Cavalry on November 1, 1861. He received four promotions before joining the First Minnesota Mounted Rangers 18 months later as a first lieutenant.

He saw action at Big Mound, Dead Buffalo Lake, and Stony Lake during the 1862-63 U.S.-Dakota War. (The first two battles occurred in later Kidder County, North Dakota, named for the lieutenant’s father.)

His enlistment expired in November 1863, but Kidder served in Hatch’s Independent Battalion of Minnesota Cavalry until May 1, 1866. After his frontier service, he apparently returned to his printer’s occupation. However, civilian life lost its appeal, and Kidder again headed to war.

Ad: Learn more about the US-Dakota War.

Custer lacks timely orders

Custer stayed at Fort McPherson, Nebraska, east of North Platte, from June 10 to 18. During that time, he met Lakota warrior Scili Kte (Pawnee Killer)* twice. Custer’s orders said to “avoid a collision” with friendly Lakota people. Kte allegedly was friendly, although an officer said he looked like a villain with “a murderous set of followers.” General William T. Sherman arrived at McPherson the day after Kte left.

Related: The Grattan Massacre‘s fallen rest in the Fort McPherson National Cemetery east of North Platte.

Sherman mistrusted Kte and changed Custer’s orders. Custer was to pursue him and separate him from the Tsisistas. Sherman ordered Custer to scout around the Forks of the Republican River. If he found hostile warriors, he would kill them and capture the women and children.

Sherman promised to meet Custer at Fort Sedgwick or send him written instructions. He didn’t.

Custer’s orders from Colonel Christopher Augur added to the confusion. Augur told Custer to return north to the Platte, and Sherman had not overridden Augur’s orders.

Kidder arrives at Fort Sedgwick

On May 18, 1867, Kidder took the Oath of Office in Washington, D.C., and became a second lieutenant in M Company of the Second Cavalry. The Army ordered him to Fort Laramie, Wyoming Territory. Among his belongings, he packed two striped flannel undershirts that his mother had made. On June 16, he arrived at Fort Sedgwick, near Julesburg, Colorado. He told his father, Judge Jefferson P. Kidder, that he was leaving for Laramie later that morning.

Instead, he was still at Sedgwick on the 28th. Kidder fit in well at the fort and had requested to remain. He expected that the Army would grant his request. On June 28, he wrote to his father. He was taking dispatches to Custer the next day and would be gone for approximately a week.

Instead, Kidder, his guide, and his men were gone forever before the week ended.

Related: Visiting the Kidder Massacre Site is one of the top 10 things to do in Goodland, Kansas.

Prelude to the Kidder Massacre: A complete communications breakdown

No one anticipated trouble. Major Joel Elliott recently visited the fort, seeking orders from Sherman. But Sherman was on a train between the fort and St. Louis. For unknown reasons, Elliott left before any message arrived from Sherman.

Sherman’s orders finally arrived two days later. Lieutenant Colonel J.H. Potter ordered Kidder to take the messages to Custer. Like Elliott, Kidder would take a 10-man escort and a guide to their expected meeting at the Forks of the Republican (near present-day Benkelman, Nebraska).

Between Elliott’s departure and Kidder’s departure, the military situation had worsened. While Elliott was gone, 500 warriors had attacked the Seventh’s wagon train near present-day Edson, and Kte had raided the Seventh’s camp. More Seventh Cavalry troopers based at Fort Wallace had fought warriors near the fort on the same day.

Apparently, no one had told Elliott to expect new dispatches, nor did anyone understand that Custer’s orders said to return north. And no one at Sedgwick knew about the hostilities away from the fort. Kidder was unknowingly headed into an indigenous uprising.

Elliott returned to Custer on June 28. Custer’s Seventh Cavalry turned away from Fort Wallace and headed northwest toward Riverside Station, near present-day Iliff, Colorado, 52 miles southwest of Julesburg.

A communication failure leads to the Kidder Massacre in July 1867

Custer’s turn was fatal for Kidder. Potter had ordered him to follow Custer’s trail until they met. Kidder’s detachment traveled during rainy weather and moonless nights. Instead of Custer, they ran into roaming warriors.

Custer turned north toward Riverside Station, southwest of Fort Sedgwick, arriving on July 5. He telegraphed for orders. Sedgwick asked, had he heard from Lieutenant Kidder?

Learning that the lieutenant was lost shocked Custer. A lost patrol likely meant a dead patrol.

Custer finds the Kidder Massacre site

Custer backtracked to the Forks of the Republican River and the Wallace Trail. On July 12, 1867, the Seventh found a dead white horse wearing a US brand. M Company rode white horses. Soon, they found another bad sign: another dead white horse surrounded by unshod pony tracks. Indians didn’t shoe their horses, while the cavalry did. The scouts determined that the other M Company troopers had started galloping, implying Indian pursuit.

The trail dropped toward Beaver Creek’s ford, and Custer’s Seventh knew the worst had happened. Buzzards circled above a small gully. Even from a distance, the stench was unbearable.

Scout William Comstock and the Seventh’s Delaware scouts followed the scavenger birds through high vegetation. They had found the Kidder Massacre site. The stench came from the decomposed bodies of Kidder and his men.

The warriors had stripped, scalped, mutilated, and disfigured the circle of troopers. Arrows peppered the corpses, and hundreds more littered the ground. The warriors had burned some troopers to torture them.

Wild animals had eaten the bodies, which were little more than skeletons. No one could identify any trooper. Only one trooper’s body had any distinguishing marks. He wore a black-and-white-checked flannel collar.

Comstock recognized Red Bead. The Lakota had scalped Red Bead as a traitor. But because he was one of them, they had not mutilated him.

Usually, the military would send an officer’s body to his family for burial, but no one could tell which body had been Kidder’s. The Seventh buried M Company in a common grave on the battlefield.

Ad: Read Custer’s account of finding Kidder.

The warriors explain the Kidder Massacre

Years later, Good Bear told George Bent the story. He and other Dog Soldiers, the Tsisistas (Cheyenne) people’s elite warriors, camped near Kte’s and Bear Making Trouble’s Lakota on Beaver Creek. One day, the Lakota ran past the Dog Soldiers. They yelled that troopers were coming, and the warriors prepared for a fight. They found dismounted troopers in a little hollow.

After the warriors found the soldiers, Dog Soldier Tobacco started riding around the troopers and shooting at them. Others followed.

The Lakota arrived, jumped off their horses, and started crawling in the grass toward the troopers. While the Lakota crawled, the Dog Soldiers continued to ride and shoot. The troopers killed Good Bear’s and Tobacco’s horses while they were riding. Red Bead asked the Lakota to let him escape, but they refused.

The soldiers were not the only casualties. The troopers killed the Sioux warriors Yellow Horse and one other. Eventually, the warriors eliminated all the troopers.

Bent said, “General Hancock’s command … in four months of active campaigning had killed four Indians. Two … were Cheyennes, and two Sioux in the Kidder [Massacre].”

Ad: Read The Fighting Cheyennes, the story of the Tsisistas’ battles to remain free.

A father finds his massacred son

Judge Kidder immediately began investigating his son’s death. He refused to accept that his son’s body was unidentifiable. Instead, he intended to bury his son’s body properly. The judge wrote Custer, including a fabric sample from his son’s undershirts. Custer said the fabric matched the collar.

The influential judge’s request to bury his son went to Ulysses Grant, then Secretary of War. Grant approved the judge’s mission on Nov. 18, 1867.

At that time, the railroad only reached Fort Hays, three days from Fort Wallace by wagon. Wallace was 47 miles from the massacre site, an estimated five days’ journey. The military wanted to bring in the bodies, but the judge refused the military’s offer. He wrote his son, Silas, “I want to see where he so bravely gave up his precious life & where he has slept these long, sad months.”

Related: Experience the Wild West in Hays.

Soldiers escort the father to his son

Comstock and soldiers under Lieutenant Fred Beecher escorted the judge to the gravesite to disinter Kidder’s body and bring it home. After surviving a blizzard, they reached the site on March 1, 1868.

They had crossed the site before, but the snow had hidden it.

Because of extreme cold, the group burned their wagons to stay alive. They exhumed all the bodies, placing Kidder’s remains in a separate box. They loaded all the remains and left for Fort Wallace.

Lieutenant Kidder goes home

At the fort, the judge prepared his son’s body for burial with the assistance of the post’s surgeons. They wrapped his body in a sheet the judge had brought, then in a white military blanket. Then they placed the lieutenant’s remains in a black walnut coffin and a pine box for transport. Twelve soldiers escorted a wagon pulled by a six-mule team and hauled the body to the railroad.

The judge noted that, except for military posts, no houses existed within 150 miles of the fort. The only civilian habitations were holes in the ground. He also noted the High Plains’ treelessness. The judge estimated that his trip home to St. Paul, Minnesota, would require about 10 days.

On March 23, the judge buried his son in the St. Paul family plot. Judge Kidder thought the massacre site was in Colorado, and the wrong state was engraved on the lieutenant’s military headstone.

The Army buries the patrol twice more

The Army buried the troopers in the Fort Wallace Post Cemetery. An obelisk honoring them still stands in the cemetery, the fort’s only remnant. When Fort Wallace closed in the 1880s, the military reinterred the soldiers’ bodies at Fort Leavenworth, where a marker honors them today.

Red Bead’s identity is lost, then found

Red Bead’s body is also interred in that same grave, but the marker lists him as an “unknown citizen guide.” A Wichita newspaper photographer proved Red Bead’s identity.

Related: Visit Fort Leavenworth, one of the state’s most haunted places.

At the massacre’s 120th anniversary, on July 1, 1987, the cemetery held a ceremony to dedicate a plaque at the marker’s foot. Diné (Apache) Chief Glittering Rainbow accepted Red Bead’s memorial flag on behalf of the Mid-America All-Indian Center in Wichita.

Related: Explore Wichita’s cultural sites, including the Mid-America All-Indian Center.

Ad: Read Randy Johnson’s book, A Dispatch to Custer.

Death stalks the Kidder Massacre’s living participants

Comstock had a year and a month to live. An assailant shot him outside a Cheyenne village in August 1868. He was supposedly interred in Fort Wallace Post Cemetery, but maybe he wasn’t.

Related: Visit the Jerry Thomas Gallery & Collection in Scott City.

Beecher had a year and two months to live. On September 17, 1868, Beecher died during the Battle of Beecher Island, which bears his name.

Elliott died at the Washita Battle on November 27, 1868, after another communication disaster. He failed to tell his commander where he was going. He and all those with him died.

In November 1868, eight months after Judge Kidder buried his son, the Kidders’ only daughter Marion died. Their son Silas outlived his parents, but Mexican law enforcement officers murdered his son, Texas Ranger Jeff Kidder, on April 5, 1908.

Ad: Read General Sandy Forsyth’s book about the Battle of Beecher Island, where he was in command.

A battle breaks the Dog Soldiers

The Fifth Cavalry surprised Dog Soldiers at the Battle of Summit Springs on July 10, 1869, and broke the Dog Soldiers’ ability to make war. Afterward, the Fifth U.S. Cavalry members captured a Dog Soldier’s sketchbook, including a Kidder Massacre drawing.

Ad: The Fifth tried to rescue captive Susanna Alderdice, but the Tsisistas killed her before the soldiers could reach her.

The fort’s surgeon finds a dinosaur

Capt. Theophilus “Thof” Turner, M.D., one of Fort Wallace’s surgeons, probably helped Judge Kidder prepare his son’s body for travel. Turner and Comstock roamed the area, hunting and collecting fossils. In late 1867, Turner, perhaps with Comstock, discovered dinosaur vertebrae in a ravine.

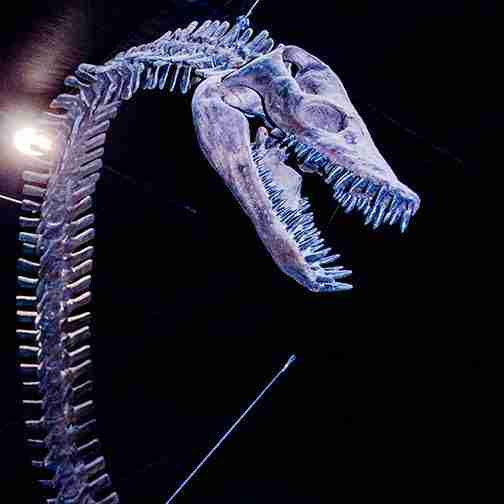

The vertebrae belonged to an Elasmosaurus platyurus. A replica of E. platyurus hangs in the Fort Wallace Museum. Turner died of cholera at Fort Wallace on July 27, 1869.

Buffalo hunters killed near Kidder site

Eight years later, unknown indigenous warriors killed three buffalo hunters near the Kidder site. Their deaths helped spark the Battle of Cheyenne Hole north of present-day Atwood.

Ad: Learn more about the Massacre at Cheyenne Hole.

Custer meets Kidder’s fate at Little Bighorn

A week short of nine years after Kidder and his men’s deaths, Custer and his men met their fate at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Capt. Myles Keogh, who commanded Fort Wallace when M Company died, was among the slain.

The Kidder Massacre site today

In 1969, 100 years after the battle, the State of Kansas erected a marker memorializing the Kidder Massacre. It stands a mile southwest of the site at Roads 28 and 77 intersection. Please sign the register in the mailbox.

The Friends of the Library of Goodland dedicated a stone monument near the site on August 3, 1969. To visit it, take the field road north of the intersection. The memorial is on the side of the hill facing the creek. Take the road at your own risk and beware of rattlesnakes and poison ivy.

The Historic Preservation Alliance dedicated silhouettes of a warrior and a soldier at the site above Beaver Creek on Sept. 28, 2003. These stand in a field to the north of the road. Lloyd Harden, the Giant Grasshopper sculptor, created the silhouettes.

In 2012, Sherman County and the Historic Preservation Alliance erected markers to guide people to the massacre site. Unfortunately, criminals vandalized some of the markers six years later. With help from Koons-Russell Funeral Home, the Sherman County Historical Society replaced the ruined markers.

A diorama at the High Plains Museum in Goodland depicts the Kidder Massacre. When you visit the museum, spin the rotors on America’s First Patented Helicopter. In 2008, the Eight Wonders of Sherman County contest named the site No. 8.

War on the Kansas plains continues until 1878

The last battle between the cavalry and the warriors, the Battle of Punished Woman’s Fork, took place south of Scott City in 1878. (Punished Woman’s Fork is on the Western Vistas Historic Byway.) The cavalry leisurely pursued the fleeing Tsisistas, allowing them to execute the Last Indian Raid in Kansas.

Driving directions to the Kidder Massacre site

To reach the site from Interstate 70, take Exit 27 at Edson and go west one mile on Old Highway 24 to County Road 28. Turn right (north) and drive about 12 miles. The state marker is on the east side of a gravel road. Go east a mile to the site. A geocacher has hidden a geocache nearby. The site is part of the Land and Sky Scenic Byway.

Ad: Order and read our book, Midwest Road Trip Adventures, which includes Land and Sky and the Kidder Massacre.

More to explore

Enjoy more of Northwest Kansas, the rest of Kansas, and the Midwest.

*-When I could determine a warrior’s name in his language, I used it.

Read more Sherman County soldiers’ stories: William Johnson, from slave to artilleryman to homesteader; Lowell Coleman and Darrell Dunkle, brothers-in-arms on France’s World War I fields.