Three weeks after Colonel John Chivington and his troopers slaughtered non-combatants at the Sand Creek Massacre, they triumphantly entered Denver. They waved Cheyenne and Arapaho scalps and other body parts on December 22, 1864. The Rocky Mountain News gushed, “Among the brilliant feats of arms in Indian warfare, the recent campaign of our Colorado volunteers will stand in history with few rivals, and none to exceed it in final results . . .”

The newspaper was right. Few rivals exceeded the Sand Creek Massacre’s final results. The ensuing war on the Great Plains did not cease until the Battle of Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890.

So what was Chivington’s alleged triumph? Peace chiefs Black Kettle, White Antelope, and others led about 750 Arapaho and Cheyenne people to a camp by Big Sandy Creek. They were trying to obey Territorial Governor John Evans and Chivington’s orders to keep the peace.

Instead, Chivington’s troops marched 40 miles overnight from Fort Lyon near Las Animas, Colorado. They attacked the sleeping village at about 6:30 a.m. on November 29, 1864. Chivington’s First Colorado Infantry and Third Colorado Cavalry attacked the camp. Chivington had never received orders to leave Denver, but he wanted the glory to bring him high office.

The Colorado militia spent eight hours murdering around 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho people, primarily women, children, and elders. They remained on the scene through December 1, desecrating the dead.

Table of contents: Visiting the site | Becoming a National Historic Site | Why the Sand Creek Massacre happened | Chivington pursues fame | Chivington’s atrocity | Revenging the massacre | Investigating the massacre | Attempting to atone | Naming the Town of Chivington | Finding the massacre site

Visiting the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site commemorates this atrocity. Don’t expect a lot of amenities at the site 180 miles southeast of Denver and 125 miles east of Pueblo. This is not a light-hearted place; it’s a place to remember, regret, and resolve “never again.” We felt the weight of history as we walked where this evil event occurred. The sense of injury — of blatant wrong — is nearly palpable.

Know before you go

The site has six things to do.

- Learn about the massacre from an interpretive ranger at 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. The 30- to 40-minute talks are stationary, not walking tours.

- Pay respects to the deceased at the Repatriation Area.

- Rest among the trees in the Visitor Use Area. The Colorado Plains are nearly treeless, so trees are a big deal.

- Walk to the top of Monument Hill.

- Look for rare birds, insects, and plants.

- Admire the High Plains landscape as you continue along the Bluff Trail. Unlike the Rocky Mountains to the west, Kiowa County’s scenery is subtle. Look for variations in the terrain and plant life.

Roxie’s reliable recommendation: Park temperatures range from over 100°F in summer to under 20°F in winter. The windy site kicks up dust and sand year-round, but especially during infrequent storms. Some of these storms produce violent tornadoes or large blizzards. Call 719-438-5916 to check road conditions, especially in wet weather. Leashed pets are allowed, but protect them from overheating.

The visitor center is in the town of Eads, Colorado, 23 miles west of the site. Its second-floor exhibit space displays people connected to the Sand Creek Massacre. To reach the massacre site, go west on Highway 96 to Chivington, then north on White Antelope Way. Drivers must traverse eight miles of gravel roads.

Becoming the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

Congress designated the Sand Creek Massacre NHS in 2000, and the National Park Service opened it to the public on April 27, 2007. In October 2022, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced the addition of 3,478 acres with significant archaeological remains of the massacre. The expansion preserves one of the National Parks’ most intact shortgrass prairie ecosystems.

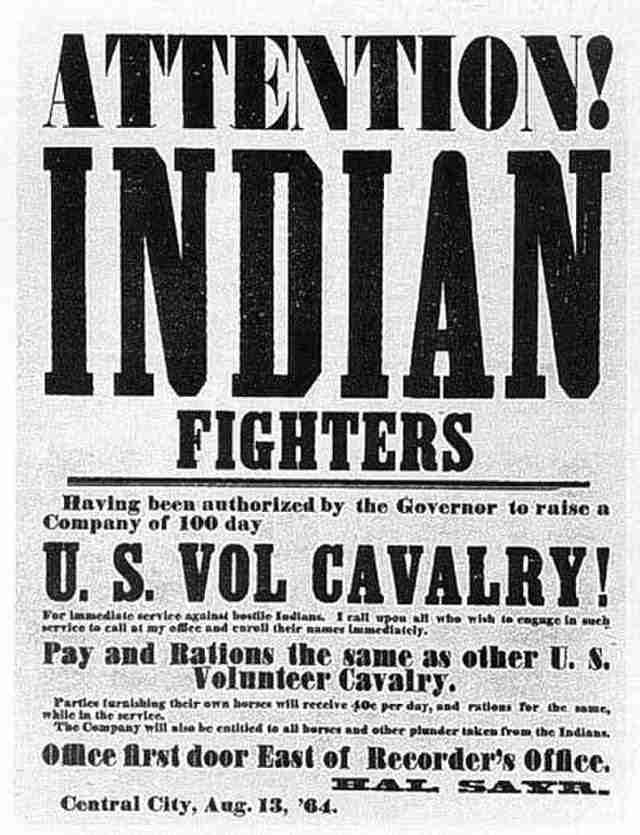

I, John Evans, governor of Colorado Territory, do issue this my proclamation, authorizing all citizens of Colorado, either individually or in such parties as they may organize, to go in pursuit of all hostile Indians on the plains…to kill and destroy, as enemies of the country, wherever they may be found, all such hostile Indians.

1864 proclamation

Why the Sand Creek Massacre happened

The advance of Euro-American settlement had pushed indigenous nations before it for centuries. In the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie, the Cheyenne and Arapaho people received the land from present-day North Platte, Nebraska, south to Lakin, Kansas, on west to the Rockies. The treaty reserving chunks of the High Plains for various tribes lasted 10 years.

Then the 1859 Pikes Peak Gold Rush brought an unceasing surge of new arrivals. They killed the bison, trampled the grass, and felled the sparse timber. The dream of an indigenous haven was over. The mining camps occupied traditional hunting grounds, depriving the indigenous nations of game. They faced starvation; therefore, they could either resist or attempt to negotiate for peace. Arapaho chief Left Hand and Cheyenne chiefs Black Kettle and White Antelope signed the 1861 Treaty of Fort Wise, ceding land in exchange for annuities (annual payments). The treaty confined the tribues to 4 million acres between Big Sandy Creek and the Arkansas River.

Roxie’s reliable report: Fort Wise was named for Virginia Governor Henry Wise, who led his state out of the Union. In 1862, the Army renamed the fort for Nathaniel Lyon, the first Union general killed in the Civil War.

Unfortunately, the agents didn’t pay the annuities and the Natives starved. In contrast to the peace chiefs, the Dog Soldiers decided to resist. Settlements in Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado suffered. By 1864, the White settlers contended with Confederate and indigenous raiders, drought, and a devastating locust plague.

John Chivington’s pursuit of fame

Chivington earned the nickname “The Fighting Parson” for delivering abolitionist sermons in Kansas Territory. The Methodist Church moved him to Omaha, Nebraska, for his safety in 1856. Then, the church moved him to Denver in 1860. When war broke out, he refused a chaplain’s commission and accepted a major’s commission in the First Colorado Volunteers.

He helped win the Battle of Glorieta Pass in March 1862, saving New Mexico and Arizona for the Union. The victory propelled Chivington into Commanding Colonel of the Military District of Colorado. When the territory achieved statehood, he hoped to become the first United States Representative from Colorado. He thought his unprovoked attack at Sand Creek would catapult him into office.

Related: Chivington owned the Manitou Springs land where the future Miramont Castle would be built.

Chivington’s new regiment of volunteer soldiers had seen no action, gaining the name, the “Bloodless Third.” They chafed at the implication that they were cowards. Shortly before their 100-day enlistment ran out, their commander led them to Sand Creek. They wreaked vengeance for the year-long war indigenous people had waged to save their lands. But as so often was the case, innocent people suffered.

Chivington’s atrocity

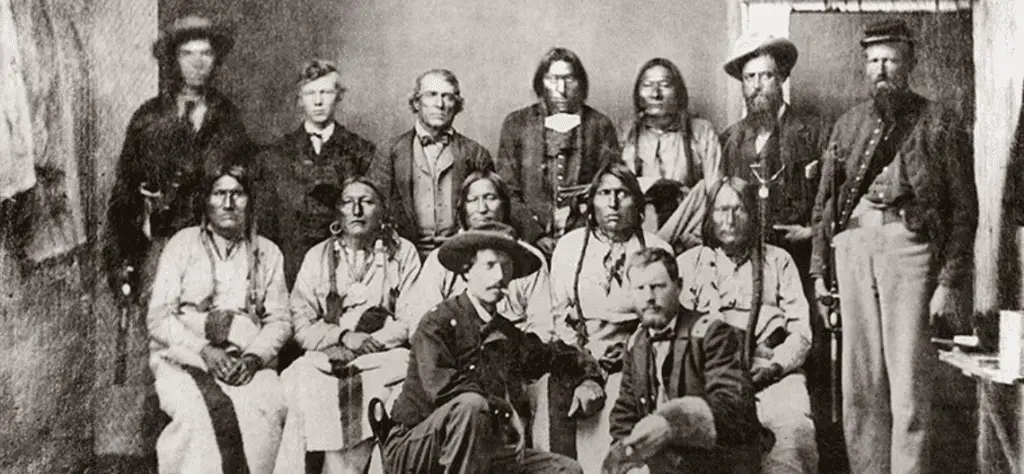

Fort Lyon’s commander Major Edward Wynkoop brought Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs to meet Evans and Chivington for peace talks at Camp Weld near Denver in September. Major Scott Anthony took command on November 2, 1864, but the orders recalling Wynkoop to Fort Riley didn’t arrive for two weeks. Anthony and Wynkoop met tribal leaders on November 15, where Anthony advised them to remain at Sand Creek.

Related: Visit Junction City, the home of Fort Riley.

Wynkoop left the fort 11 days later while Chivington was en route from present-day Boone, Colorado. The Bloodless Third arrived two days after Wynkoop left. Chivington forced Robert Bent to guide them to Sand Creek, where his brothers Charlie and George Bent were living. They were the sons of noted trader William Bent and his Cheyenne wife Owl Woman.

I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians.

John Chivington

The Bloodless Third lost the Bloodless title the next morning.

When the cavalry arrived, Black Kettle hurriedly raised the Stars and Stripes above his lodge with a white flag beneath. The waving American flag would surely show that they had the protection of the US Army. The troops fired carbines and cannons instead.

White Antelope ordered the soldiers to stop in English, but a soldier shot the 73-year-old at point-blank range. Black Kettle fled the camp but returned to rescue his seriously wounded wife. She suffered nine bullet wounds. Other desperate villagers tried to dig holes in the sand for protection, but nothing saved them.

Revenging the massacre

The survivors fled northeast in the bitter cold to the Cherry Creek Encampment northwest of present-day St. Francis, Kansas. Many of them lacked adequate clothing, including shoes. George and Charlie Bent survived the massacre and renounced their White ancestry. At the camp, the Cheyennes plotted a vengeance campaign with other tribes.

In January 1865, Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors left Kansas through Devil’s Gap in the Arikaree Breaks, heading to Julesburg, Colorado. They raided Julesburg, killing 15 Camp Rankin soldiers and some civilians and emptying Julesburg’s warehouses. Three weeks later, the warriors burned Julesburg to the ground after looting the restocked warehouses again.

Related: Lieutenant Lyman Kidder left Fort Sedgwick, Camp Rankin’s successor, and died in the Kidder Massacre on Land and Sky Scenic Byway.

Soldiers from Fort Cottonwood (later Fort McPherson) attempted to stop the raids but could not catch the raiders. General Robert Mitchell asked every ranch and military outpost from Fort Kearny to Denver to start prairie fires at sundown on January 27. Nebraska south of the Platte River and west of Fort Kearny burned. The fires devastated habitat and killed wildlife. No game meant starving Natives.

Related: Visit Fort McPherson National Cemetery near North Platte.

Charlie Bent later died fighting the Fifth Cavalry at the 1869 Battle of Summit Springs near present-day Sterling. The battle destroyed the Cheyennes’ resistance in the Southern Plains.

Investigating the massacre

The attack on Sand Creek appalled Captain Silas Soule. He viewed the massacre as a betrayal. He and his troops stood aside and bore witness instead. Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer reported the massacre to Wynkoop. In turn, Wynkoop distributed the reports to various military commanders and political figures. Their bombshell reports sparked a Congressional investigation.

Chivington resigned his commission in January, escaping military jurisdiction. Unfortunately, Soule paid for bearing witnesses. Cavalry troopers Charles Squier and William Morrow shot him in April 1865 but were never tried. Chivington died in Denver in 1894.

Roxie’s reliable report: The annual Spiritual Healing Run/Walk commemorates those who died on that tragic day. Every November, Cheyenne and Arapaho conduct a ceremony at the Sand Creek site. After the healing run from Sand Creek to Denver, the organizers read Soule’s letters. The run began in 1999.

“Wearing the uniform of the United States, which should be the emblem of justice and humanity … [Chivington] deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre.”

Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

The Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War published its Sand Creek Massacre report in July 1865. It condemned Chivington’s actions and recommended Evans’ removal as territorial governor. President Andrew Johnson removed Evans the next month.

Attempting to atone for Sand Creek

The federal government’s representatives signed the Little Arkansas Treaty with the Cheyenne and Arapaho on October 14, 1865, near Wichita. Wynkoop was the Indian Agent for the Cheyenne and Arapaho at the time. The treaty included monetary reparations payments for the Sand Creek Massacre’s “gross and wanton outrages.” Land reparations included 640-acre grants in Colorado for people including the Bent children and John and Amache Prowers‘ family. Amache’s father Lone Bear (Ochinee) had died in the massacre.

Related: Camp Amache, the Japanese internment camp, bears Amache Prowers’ name.

The treaty’s promised Oklahoma reservation included 320-acre land grants to Black Kettle and other leaders at Sand Creek and 160-acre grants to those who lost spouses or parents. The treaty lasted two years until the disastrous Medicine Lodge Treaty superseded it. Despite numerous lawsuits, the government never paid the monetary reparations.

Roxie’s reliable report: Despite Black Kettle’s continued peace-making efforts, he died when George Custer and the Seventh Cavalry attacked his village at the Battle of the Washita River.

Related: Custer and part of the Seventh later died at Southeast Montana‘s Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Naming the Town of Chivington

Not everyone felt embarrassed by the massacre. Railroad companies often named towns in alphabetical order from east to west. The Missouri Pacific stations started in Colorado with Arden (near Sheridan Lake), followed by Brandon, and then Chivington. The railroad located its division roundhouse at Chivington in October 1887. The railroad boom town grew to over 1,500 inhabitants in 1887 and 1888. The local newspaper was called The Chivington Chief. Eventually, it became a ghost town.

Finding the Sand Creek Massacre site

The precise Sand Creek Massacre site soon became as controversial as the atrocity itself. Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell proposed the site as a national park, but no one knew its actual location. The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Study Act of 1998 directed the Secretary of the Interior to find the site and designate it as a unit of the National Park System. Congress required the park service to work with the indigenous nations and the State of Colorado.

Apologizing for Sand Creek

Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper apologized to the descendants of the Sand Creek Massacre survivors on behalf of the people of Colorado in 2014.

After years of effort, the US Board of Geographic Names changed Mount Evans to Mount Blue Sky in 2023. The Arapaho are the Blue Sky People, and the Cheyenne hold an annual renewal-of-life ceremony called Blue Sky.

Remembering the past enables us to eliminate or at least mitigate future mistakes. That’s the purpose of visiting Sand Creek.

Where to stay

Please pin this post.