The gorgeous three-story red-brick Watkins National Bank Building stands out along Downtown Lawrence’s Massachusetts Street. Lawrence financier Jabez Bunting Wilson built one of the city’s finest Richardsonian Romanesque buildings as a marketing tool. The building later became the Watkins Community Museum of History and eventually the Watkins Museum of History.

Explore Lawrence sponsored my visit, but all opinions are mine. If you use our affiliate links, including Amazon Associates and Stay22, to make a purchase, we might earn a small commission for our time and website costs (at no additional cost to you). These links are always disclosed.

The opulent 1888 edifice displayed the Watkins Land Mortgage Company’s success. J.B. Watkins died in 1921, and his wife Elizabeth inherited his estate. The couple had no children, so she poured her philanthropy into Lawrence. Among other projects, she funded a pair of scholarship halls at the University of Kansas, the Watkins Memorial Hospital, and the Lawrence Memorial Hospital.

Elizabeth donated the Watkins Building to the City of Lawrence eight years after J.B. died. At first. the building served as the Lawrence City Hall. Later, the Douglas County Historical Society, a private non-profit organization, opened the Watkins Museum of History in 1975.

Roxie’s reliable report: Admission is free at the Watkins Museum, but donations are gratefully accepted. The museum also schedules numerous public events.

Examine an architectural treasure at the Watkins Museum

Before you indulge your love of history with the artifacts and interpretations in the Watkins Museum of History, look at its exquisite architectural details. The masons used red mortar to create a smooth building façade. Look for the careful brick placement above the second floor’s arched windows. The Boston Terra Cotta Co. supplied ornaments for the building’s window ledges and roof pinnacles.

Inside, a first-floor mosaic displays the Watkins name. An elaborate 25-foot chandelier hangs from the ceiling with detailed plasterwork above it. Stained glass windows illuminate the staircase, and metalworkers crafted bronze shields emblazoned with JBW monograms for the staircase’s frame.

The Watkins National Bank originally inhabited the second floor, where cast plaster moldings enhance the second floor’s ceilings. Mosaics cover the floors, while Tennessee marble and Mexican onyx form the wainscoting. The top floor’s ceilings are 20 feet high with 12-foot-tall windows.

Experience the fascinating history of Douglas County at the Watkins Museum

An elaborate bank teller’s counter welcomes guests on the Watkins Museum’s first floor. The counter contains 14 marble and onyx varieties. The counter’s lower section is original, but the stained glass and steel upper section is not. However, the design closely matches the original.

A painting of Quantrill’s Raid comes next, displaying Lawrence’s suffering and resilience during Bleeding Kansas and the American Civil War’s violence. The New England Emigrant Aid Company founded Lawrence in 1854, and the city became a free-state stronghold.

Related: Sheriff Samuel Jones from Lecompton burned the Eldridge for the first time in 1856.

Quantrill burned the Eldridge Hotel for the second time, but the museum displays a candlestick rescued from the hotel before Quantrill burned it in 1863. A hotel table and chairs are on the third floor. The raiders murdered 160-190 men and boys. (The Lawrence city seal depicts a phoenix rising from the Eldridge Hotel’s ashes.)

In response, Union General Thomas Ewing issued Order No. 11, which forced four Missouri counties’ residents to move into Kansas City. Ewing’s order limited the guerillas’ ability to gather supplies from their friends and families. The bitterness on the United States’ western border continued after the war as the Lawrence survivors and the Quantrill raiders continued to hold reunions.

Related: The territorial legislature met in the Babcock & Lykins Building, which Quantrill also burned.

Roxie’s reliable report: The heritage of Douglas County includes the pieces of Old Sacramento on the first floor. Free-staters used the cannon against pro-slavery forces. After the war, the community used it during celebrations until it exploded in 1896.

Continue exploring the museum’s stories

The local history museum’s exhibits continue with a look at the Douglas County Underground Railroad and John Brown.

Charles H. Langston and his wife, Mary Patterson Leary Langston, settled in Lawrence. Her first husband, Lewis Leary, fought and died with Brown at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The Langstons raised their grandson Langston Hughes, who became a noted poet.

View more fascinating stories of the people who defined Lawrence, like Maggie Herrington, an 1860s schoolgirl. Inhale the scents of “old-time smells,” like manure, smoke, grass, and sand, then count 1900s-style money using the Watkins National Bank’s original cash drawer.

Related: Visit the top 23 Kansas civil rights sites and John Brown in Osawatomie.

Step back in time to an earlier Lawrence’s material culture with storefronts, a Milburn Electric Car, a carriage, and a Victorian playhouse.

See Lawrence in the movies

Recall Lawrence’s role in “The Day After,” The Dark Command, and BlackkKlansman (ads). Over 75,000 people came to the Downtown Lawrence premiere of The Dark Command. The movie loosely portrayed Quantrill’s Raid with “William Cantrell” as the villain. However, the movie was shot elsewhere. Even so, John Wayne, the star, and Gene Autry, who wasn’t in the movie, came for the event. Roy Rogers was in the movie, but he didn’t sing. Look for the autographed cowboy hat with signatures from Wayne, Rogers, Autry, and George “Gabby” Hayes.

Related: Visit John Wayne’s birthplace in Winterset, Iowa.

University of Kansas professor Kevin Willmott bought a tuxedo from Weaver’s Department Store for the 2019 Academy Awards. He returned to Lawrence with an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay for BlackkKlansman. Spike Lee, Charlie Wachtel, and David Rabinowitz shared the award. The tuxedo and a lapel pin are on display.

ABC mostly filmed “The Day After,” a dystopian 1983 TV movie about life after a nuclear bomb, on location in Lawrence. Over 100 million people watched the show, and the museum displays pieces of the movie’s sets.

The Watkins Museum and the Cradle of Basketball

No Lawrence public history museum can omit basketball. Kansas Jayhawk Wilt Chamberlain helped to combat segregation by visiting segregationist businesses. No business wanted to turn away the KU hoops star, so segregation lost adherents. Meet the all-Black Lawrence Promoters, who played during nearly 33 years of segregation, then watch vintage videos of the Jayhawks.

Pose with a scale model of Coach Forrest C. “Phog” Allen, the Father of Basketball Coaching. The full-size Allen sculpture stands in front of Allen Fieldhouse. Basketball inventor James Naismith is, ironically, the Jayhawks’ only coach with a losing record. Ponder that fact while looking at his desk.

Roxie’s reliable report: Look for Lynette Woodard, who still holds the all-time women’s basketball scoring record. She set that record while shooting with a man-size ball. The rules didn’t allow the smaller women’s basketball then. Woodard became the first female Harlem Globetrotter.

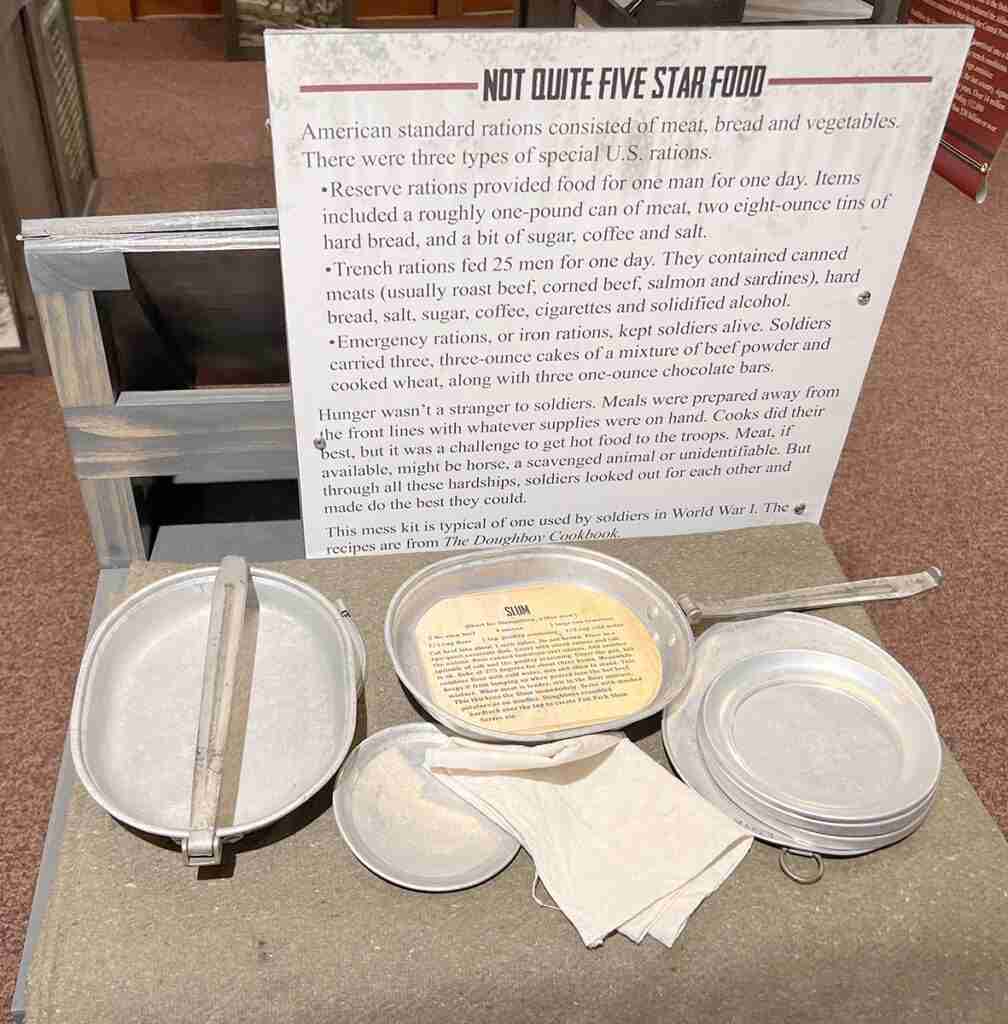

Over There: World War I and the Watkins Museum

When we visited, the Watkins had a World War I exhibit in the basement. The exhibit discussed the impacts of the war, like Black soldiers’ return to Lawrence in July 1919. Their return sparked the end of segregated classrooms.

Related: Read about two friends’ sacrifices in World War I.

Charles D. Barger of Galena, Kansas, earned the Medal of Honor on October 31, 1918. Barger was 3 when the state sentenced his father, a Staffleback gang member, to life in prison. His mother left him in an orphanage, from whence he was adopted.

During the war, Barger and Jesse Funk rescued two officers and an enlisted man from no-man’s land. The rescue required two 500-yard trips under continual machine gun fire. General John J. Pershing awarded them the Medal of Honor. Barger’s heroism earned 15 total medals, but he struggled after he left the service.

Related: Ma Staffleback’s brothel is one of our haunted Kansas places.

The Japanese Friendship Garden

The Japanese Friendship Garden is on the museum’s north side, a quiet oasis in Downtown Lawrence. The 90 by 92-foot garden contains a wisteria-covered arbor, Japanese maples, Yoshino cherry trees, yews, bamboo, juniper, and mugho pines with flowers like azaleas, spirea, viburnum, Siberian iris, and peonies.

Lawrence’s sister city, Hiratsuka, Japan, sent representatives to help design the project and donated a lantern and a 15-foot-tall stone tower for the garden. The sister cities each donated $5,000 on their sisterhood’s fifth anniversary. The Sister City Garden Gala raised another $15,000-plus, and volunteers created the garden in their free time, showing their community support.

Roxie’s reliable recommendation: Stroll down Massachusetts Ave. to one of the many delicious restaurants after touring the museum. Of course, anyone interested in Lawrence’s history must stay at the Eldridge Hotel. Campers should stay at the Kansas City West/Lawrence KOA.