Enter the world of the horse-mounted soldiers, the Big Red One, and experience early Kansas history in the four Fort Riley Museums. The US Cavalry Museum, the First Infantry Division Museum, the Custer House, and the First Territorial Capitol provide aspects of the history of Fort Riley. The fort near Junction City recently renovated the cavalry and First Infantry Division’s museums.

Related: Explore 41 things to do in Junction City.

Visit Geary County sponsored my visit, but all opinions are mine. If you use our affiliate links, including Amazon Associates and Stay22, to make a purchase, we might earn a small commission for our time and website costs (at no additional cost to you). These links are always disclosed.

The fort is half an hour from Manhattan (MHK), the nearest commercial airport. Fort Riley is two hours west of Kansas City on Interstate 70. The museums are housed in some of the fort’s oldest buildings.

Book your flight and more.

Table of contents

General information | US Cavalry Museum | First Infantry Division Museum | Custer House | First Territorial Capitol | Driving tour

How to visit Fort Riley

All Fort Riley guests must be approved through the Visitor Control Center (VCC) for a smooth visit. Department of Defense ID card holders need no temporary pass. To expedite the process, submit a pass application in advance.

Online passes are only available for American citizens with valid REAL ID-compliant identifications and a mobile phone. The VCC will text their approval or denial, but will not email a pass. Request one 30 days or less in advance but at least 24 hours before your visit. Approved visitors should present their identifications at any Fort Riley gate.

If you didn’t apply in advance, don’t worry. The VCC is there to help. Stop at the Henry Gate on Henry Avenue for a temporary Fort Riley access pass. Unescorted visitors must be at least 18, explain their visit, and provide approved identification. Use a driver’s license complying with REAL ID standards or a valid US passport. Children may visit with adult accompaniment. Without pre-approval, expect a 10-minute average wait time. Expect longer delays when traffic is high.

Roxie’s reliable report: REAL ID driver’s licenses have a five-pointed star on them. Cell phone usage is prohibited while driving on the fort.

Why visit the Fort Riley Museums?

Historic Fort Riley in the Flint Hills has played a crucial role in America’s defense since its founding. The military base’s museums feature state-of-the-art interactive exhibits explaining the troops’ service and sacrifices. A visit provides a greater appreciation for the Army’s role.

Hours, parking, and accessibility

The Cavalry and 1st Division museums are open Monday through Saturday from 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and from noon to 4:30 p.m. on Sundays. The Custer House is open from Memorial Day to Labor Day from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., except for its Sunday hours, 1-4 p.m. All three museum buildings are within easy walking distance of each other at 205 Henry and 24 Sheridan Avenues. The field between them is filled with monuments, artillery, and historic military vehicles.

Some parking is in front of the museums, and street parking is in front of the Custer House.

The First Territorial Capitol at 693 Huebner Road is open from mid-April to mid-October from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesdays to Saturdays and 1-5 p.m. on Sundays.

All the museums except for the Custer House are accessible.

Fort Riley’s beginnings

Captain Robert Chilton’s First Dragoons selected the Kansas River’s headwaters as a new fort site in 1852, two years before Kansas became a territory. During the next spring, the Sixth Infantry began building Fort Riley. Three museums document the history of Fort Riley and the Army units stationed there. The first territorial governor summoned the scandalous Bogus Legislature to meet in the First Territorial Capitol. However, its reign as capital was brief.

Related: Travel the Kansas Territorial Capital Trail.

U.S. Cavalry Museum at Fort Riley

The Cavalry Museum offers a historic tour of the cavalry from its origins through its roles in American history. The nation’s horse-mounted soldiers served from the Revolutionary War to World War II. Horses were mission-critical to armies before motorized transport became available. Horses hauled supplies, artillery, and messages. Heavy cavalry units broke enemy formations. The cavalry transitioned into armor when motorized vehicles took over the horse’s role.

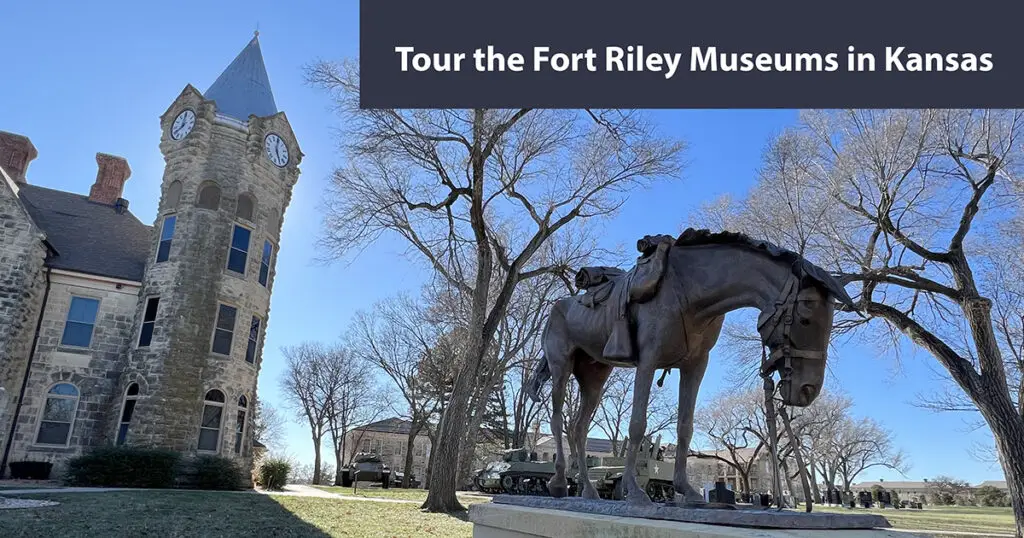

The native limestone building is one of the four oldest structures on the post. Its south wing dates to 1855, when it was the post’s hospital. In 1890, it became the Cavalry School Administration Building, and a turret clock tower was added as part of the renovation.

Artifacts to look for in the museum

Every military museum displays uniforms and weapons. Instead, the Cavalry Museum exhibit galleries start with the cavalry horse and its equipment. Then guests see 19th-century European cavalry uniforms and weapons, including the British hussars. Hussars were light cavalry mounted on fast, light horses. Don’t miss their czapka (pronounced SHAP-ka) headdress, which looks like a skullcap paired with an academic mortarboard. A brass plaque protected their foreheads while leaving the backs of their heads unprotected.

While weapons and uniforms are plentiful, look for more.

The greatest light cavalry

However, the world’s greatest light cavalry did not come from Europe. Instead, the Indigenous peoples of the American Great Plains held that title. The horse soldiers from the Pawnee, Crow, and Arikaree nations rode with the US Cavalry against their ancient enemies, the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho.

Artifacts like a dress embellished with tiny shells tell the Plains Natives’ stories.

After discussing American cavalry in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the exhibits reach Fort Riley. First, guests learn about the fort’s namesake, General Bennet C. Riley. He led the Santa Fe Trail’s first military escort in 1829. The fort was supposed to guard the overland trails and keep the peace with Indigenous people. Unfortunately, Fort Riley’s soldiers could not avoid entanglement in the Bleeding Kansas tragedy. Instead, in 1858 they helped break up the free-state legislature in Topeka. The Kansas guerilla war was the Civil War’s opening act.

The cavalry played a major role in the Civil War. As in all wars, Civil War soldiers spent much of their time in camp. One of the dioramas shows camp life, with a soldier playing his cigar-box fiddle.

The Buffalo Soldiers

The Buffalo Soldiers, Black men commanded by White officers, arrived at the fort in 1868. Their units were stationed there at times well into the 20th century. During their service, the fort supported the Army in the Indian Wars and became the army’s cavalry school.

Buffalo Soldiers served in the 1916-17 Punitive Expedition in Mexico. The Army chased Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, but never caught him. Moreover, the expedition was the last to use horse-mounted cavalry and the first to use airplanes.

Related: The Army established the Buffalo Soldiers at Fort Leavenworth.

Cavalry in the movies and on TV

After viewing the real Army, check out the Cavalry Theater, showing cavalry-themed movies. Of course, the version Hollywood showed in John Wayne’s movies (ad) wasn’t reality. Most frontier forts didn’t have stockades, and the cavalry rarely got to charge with sabers drawn. A vintage television runs cavalry-themed TV shows like F Troop (ad).

Related: Visit the John Wayne Birthplace Museum in Winterset, Iowa, also home to the Bridges of Madison County book and movie (ads).

Cavalry in the 20th century

After the shows, watch World War I soldiers reloading a machine gun in a diorama. World War II Jeeps and tanks are on display. However, the horse soldier returned during the post-World War II occupation of Germany. The Constabulary’s Circle C Cowboys used 300 horses along with motorized vehicles to patrol Germany.

Look for the art displays in the final exhibits, including Fredric Remington and contemporary artists Don Stivers and Don Troiani. Before you go, dress up in a cavalry outfit, a vintage dress, or the perfect selfie. For the perfect prop, ride a wooden horse on a McClellan saddle.

1st Infantry Division Museum at Fort Riley

After riding with the cavalry, walk down the sidewalk to the 1st Infantry Division Museum. You’re about to learn the story of the division, one of the US Army’s major commands. After a long renovation, the museum reopened on April 26, 2024. Sergeant First Class James Sharp, a World War II veteran, attended the grand opening as a guest of honor.

The division, nicknamed The Big Red One (BRO), was organized on June 8, 1917. It was the Army’s first permanent division. The BRO was the first to fight in France during World War I and the last to return home. The division began World War II in North Africa and Sicily before coming ashore at Omaha Beach on D-Day. Afterward, the BRO served in all of America’s wars except the Korean Conflict. Instead of going to Korea, they guarded Western Europe. A display near the museum’s entrance honors the division’s 37 Congressional Medal of Honor recipients.

Artifacts to look for in the museum

A photograph of a United States soldier from each era accompanies demographic information about the Army. For example, 37 percent of the World War I soldiers were illiterate. Fourteen percent of the US population served in World War II. Many more worked in defense-related industries.) The average American infantryman in the Vietnam Conflict endured 240 days of combat in a year. The average Iraq War soldier was 28 years old, and the average officer was 35.

Under “No Sacrifice Too Great,” a Battlefield Cross (rifle, helmet, dog tags, and boots) represents the division’s fallen from each war.

War inflicts misery and the rat-infested, flooded trenches of World War I were especially miserable. The trench exhibit only hints at the soldiers’ suffering.

A large diorama shows the landing at Omaha Beach during the Normandy Invasion on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Look for the sinking landing craft surrounded by soldiers struggling to survive. At one end, Rudder’s Rangers assault Pointe du Hoc.

Related: Twenty men from Bedford, Virginia, died on Omaha Beach. Now the National D-Day Memorial is in Bedford.

Watch Sharp reminisce about his time as a guard during the Nuremberg Trials. The Allies tried the highest-ranking surviving Nazis there, with Sharp having a ringside seat.

Another diorama shows an explosive ordnance disposal technician disarming a cell phone turned into an improvised explosive device (IED). IEDs were a common threat to soldiers during the Global War on Terror in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Custer House at Fort Riley

Ironically, George and Libbie Custer never lived in the Custer House. A kitchen fire destroyed their former home during the 1930s. However, the current house museum is the only 1850s officer’s quarters remaining. The furniture inside dates to the Custers’ time at the fort.

Before Fort Riley, Libbie had accompanied her husband to some uncomfortable postings. Therefore, the Kansas post was a refreshing change. She wrote, “We are living almost in luxury … Our large kitchen and dining room are quite the pride of my life.”

Related: The Custers lived at Fort Abraham Lincoln near Bismarck, North Dakota, before his death at the Battle of Little Bighorn in Southeast Montana.

The Custers enjoyed entertaining, and the parlor and dining room saw many happy occasions. China and silver adorn the dining room table, while a piano is ready to provide entertainment in the parlor. The piano’s legs detached to fit in a wagon. The railroad had yet to reach the fort when the Custers arrived, so they relied on wagons. A portable desk like Custer used in the field, a chair made of antlers, and a bugle are in an upstairs bedroom.

Roxie’s reliable report: Look for monuments to the BRO’s component units next to the museums. A Twin Tower-shaped monument honors “those deployed through Fort Riley in support of the Global War on Terror.”

Fort Riley’s First Territorial Capitol of Kansas

Territorial Governor Andrew Reeder had mixed motives when he moved the territorial capital to Pawnee. The new town adjoined the Fort Riley Military Reservation. Reeder hoped to lessen the threat of invasion by the Border Ruffians by moving the capital away from the Missouri border. Fort Riley’s commander, Major William Montgomery, became the Pawnee Town Association’s president. The group gave Reeder a large chunk of the town’s land. They built a territorial capitol building next to the Kansas River.

The first territorial legislature arrived at the capitol on July 1, 1855. Soldiers at the fort were dying from cholera, and the capitol building and town were unfinished. The builders dug the exterior native limestone blocks from a bluff to the north. The House met on the lower level with the Senate on the upper.

The legislators were not pleased. The majority of them supported slavery, and they were far from their Missouri base. They removed the free-state legislators, earning them the Bogus Legislature title. On Independence Day, the legislature voted to return to the Shawnee Indian Mission to ensure slavery’s victory. Eventually, Lecompton became the territorial capital.

Related: Visit historic Lecompton, Kansas.

The end of Pawnee

By the end of the year, Reeder and Montgomery had lost their jobs, and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis had evicted Pawnee’s settlers. The Army razed every Pawnee building except the former capitol. The Army used the building until its roof blew off in 1882. The Union Pacific Railroad renovated it in 1928. It’s now a state historic site.

The two-story building looks much as it did in 1855. The site features exhibits about Bleeding Kansas, Kansas in the Civil War, and items from the territorial legislature.

Experience the Fort Riley Driving Tour

Brevet Major Edmund Ogden oversaw the fort’s construction. The cholera that scared the legislators killed about 70 people including Ogden and his wife. His monument and the post’s cemetery are part of the Fort Riley Driving Tour (PDF).

Among other tour monuments, the Seventh Cavalry erected the Wounded Knee Monument to honor the 25 troopers who died there. However, the Seventh killed at least 150 Lakota people. Some estimates run to 300 Lakota dead, many of them non-combatants. Instead of a battle, it was a massacre. The Army relieved Colonel James Forsyth of command but reinstated him after an investigation. Twenty of the troopers received the Congressional Medal of Honor. In contrast, 30 people earned the Medal from 1993 to 2018. Members of Congress have tried to rescind the Wounded Knee Medals to no avail.

The tour also passes Camp Funston. The World War I training camp became notorious as the ultimate super spreader for the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. General Leonard Wood erected the Great War Memorial to honor Camp Funston’s soldiers.

Roxie’s reliable report: The post prohibited Black soldiers from living there. Instead, they lived in the Pawnee Park development. The Buffalo Soldier Monument honors the Black soldiers who served at the fort. It’s part of the Black History Trail of Geary County.

While in Geary County, don’t miss Milford Lake and Milford State Park. The lake is the state’s largest reservoir.

Enter the warrior zone at Fort Riley and learn more about your military history.

Book your stay in Geary County.

Book your trip

Let’s add your trip to your calendar! Roxie’s reliable recommendations will get you ready.

Insure your trip:

Plan your flight and book your tickets:

- Aviasales

- CheapOAir

- Priority Pass (provides frequent travelers with airport lounge access around the world)

Plan your overnight accommodations anywhere from national chains to private homes with:

Save on activities, from tours to attractions: