The Union came for Mobile, Alabama, in August of 1864. They attacked because the Port of Mobile was the last major Confederate port still open in the Gulf of Mexico. The Union blockade was slowly strangling Confederate trade as the Civil War continued. As more Southern ports fell, the rebels could not export cotton.

At the beginning of the American Civil War, General-in-Chief Winfield Scott advocated for a full blockade of Southern ports and an attack down the Mississippi River. His detractors nicknamed this plan “The Anaconda Plan.” Instead, they wanted a glorious single battle to end the conflict. The far-sighted Scott had the right idea.

The blockade prevented the Confederates from selling cotton in exchange for munitions, salt, and other needs. Even worse, Confederate blockade runners could not bring bulky goods, so shortages plagued the Confederate population. Fort Morgan had to prevent Mobile’s fall to keep supplies flowing.

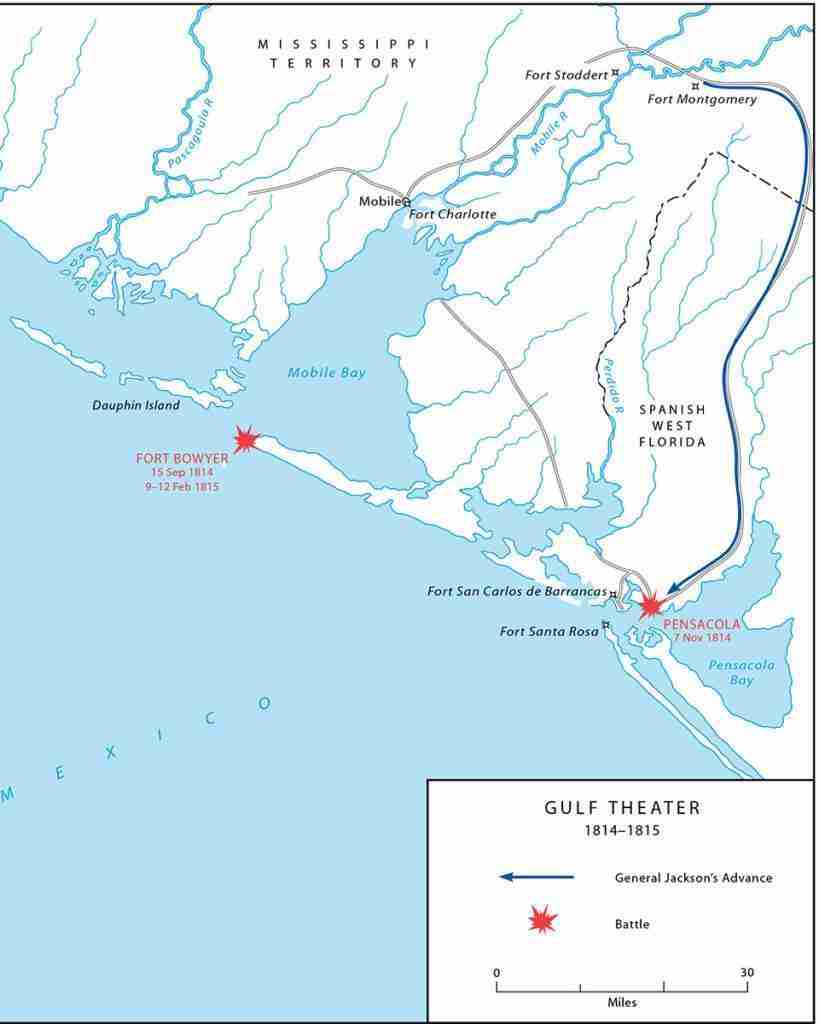

Before the fort’s star turn in the Civil War, its predecessor, Fort Bowyer lost the War of 1812’s final battle just before peace came.

Related: The Battle of Tippecanoe was a prequel to the War of 1812.

If you use our affiliate links, including Stay22, to make a purchase, we might earn a small commission for our time and website costs (at no additional cost to you). These links are always disclosed.

Table of contents

Things to do | Birding | Scenery | Beaches | Fishing | Eat and stay | Battle of Mobile Bay | Fort Bowyer | Building Fort Morgan | Confederate takeover I Post-Civil War | The World Wars | State historic site

The 19th-century fort on Alabama’s Gulf Coast protected Mobile Bay from 1834 through World War II. It’s now Fort Morgan State Historic Site, 22 miles west of Gulf Shores on State Highway 180. Visit it for the history, the views, fishing, birding, and the beach. The Mobile Bay Ferry reaches it from Dauphin Island. The museum, restrooms, and ground level of the fort are accessible to individuals with physical disabilities. Restrooms are at the ferry landing and the museum. The landing offers a snack bar at the ferry landing.

Related: Enjoy numerous outdoor activities at Gulf State Park.

Things to know

Wear sunscreen and a broad-brimmed hat with a string to prevent the wind from taking it. Drink plenty of water in the summer. Watch your step because the ground around the fort is fairly level, but bricks are missing or broken in some walkways. The fort is an excellent place for family activities, but please prevent your children from getting too close to the edges of the walls.

Roxie’s reliable recommendation: Purchase admission in advance to save time. The fort is a Blue Star Museum, which means free admission for active-duty military personnel and their families between Memorial Day and Labor Day. Allow about 2 hours to see the fort.

What to do at Fort Morgan State Historic Site

History buffs will want to tour the fort, its concrete artillery batteries built between 1895 and 1904, the museum explaining Mobile Point’s military history from 1814 to 1945, and the exterior of historic military buildings from 1898 to 1910. Shop at the museum gift shop for collectibles, toys, specialized books, and gifts.

Fort Morgan is one of the best examples of a 19th-century masonry star fort. Salt stalactites slide down the high-arched ceilings and walls of the casemates. Concrete intrusions held the batteries installed from 1899-1900. The powder magazines retain the davits used to hoist ammunition to the gun crews above. Look for the pair of 24-pound Civil War flank defense howitzers. Ironically, peaceful wildflowers now bloom in the batteries’ cracks.

The Fort Morgan Museum, outside the fort’s sally port, uses numerous artifacts to explain the fort and its history. The fort holds annual events, including a Battle of Mobile Bay commemoration and an Independence Day celebration.

Imagining the fort’s past

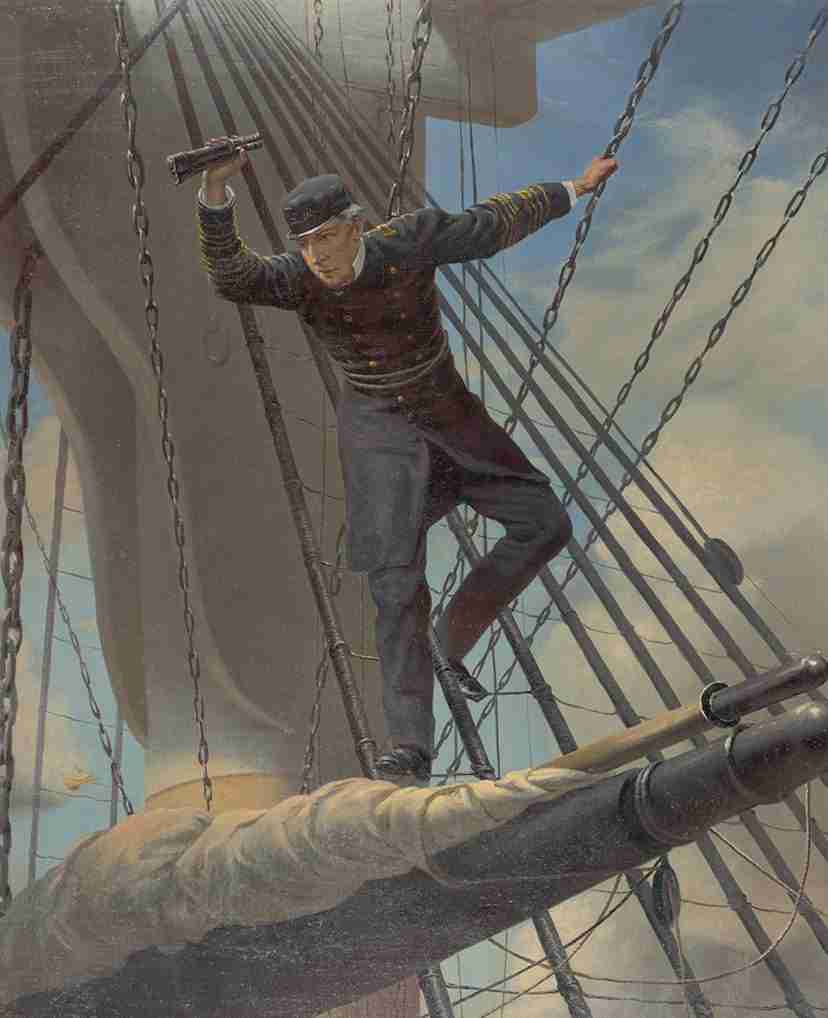

While standing on the star-shaped fort’s walls, I imagined the chaos and carnage of the Battle of Mobile Bay below the military fort. In my mind’s eye, I watched Union Admiral David Farragut lashed to his flagship’s rigging, screaming at his pilot, demanding that his fleet ignore the evident danger and press on to victory.

I envisioned the British forcing Fort Bowyer’s surrender, only to have a British ship deliver a message that the War of 1812 was over.

As I walked around the fort’s interior, my mind’s eye saw the enslaved and free workers constructing a masterpiece of brickwork to defend Mobile Bay.

Related: The Union Army and Navy cut the Confederacy in half when Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson, Louisiana, fell in July 1863.

Birding at Fort Morgan

Bring your birding binoculars, as Fort Morgan is an important migratory bird stopover, part of the Alabama Coastal Birding Trail (PDF). The American Bird Conservancy designated the fort a Globally Important Bird Area. The fort is a birding paradise, especially when adverse weather forces birds to land. Hundreds of migrating hawks appear in the fall, while waterbirds and sparrows arrive in the winter. Summer is the slowest season, but it can be good for terns.

The Stables near Fort Morgan State Historic Site’s eastern sea wall’s entrance kiosk is a prime spot for migratory birds. Look for the Hummer/Bird Study Group‘s banding station in the area each April and October.

Related: Visit Cheyenne Bottoms, a prime birding destination near Great Bend, Kansas.

Scenic Fort Morgan

Steep stairs ascend to the top of Fort Morgan State Historic Site’s walls at the end of scenic Fort Morgan Peninsula. From there, revel in unobstructed views of Mobile Bay, the fort’s parade ground, and the natural gas wells south of Dauphin Island.

Even steeper stairs inside the star fort have no exterior guardrails. Ascend and descend with care.

Beaches on the peninsula

Nearly half of Alabama’s beaches are on the 14-mile Fort Morgan Peninsula. Five types of beach access are available from Bon Secour National Wildlife Refuge‘s eastern boundary to the peninsula’s west end at Mobile Point. Each has separate guidelines for use, activities, and legal jurisdictions. Download the guide for details. Beach access from the fort is across the parking lot from the museum.

Roxie’s reliable report: Archaeologists discovered an abandoned ancient canal cut through the Fort Morgan Peninsula in 2019.

Fishing locations

Dixey Bar is a sandbar stretching from the Fort Morgan Peninsula. It’s a prime redfish destination from September through December. Try kayak fishing; launch your kayak from the fort’s Mobile Bay side. Fort Morgan Pier is known for its flounder fishing. Navy Cove, north of Fort Morgan, is quieter than the bay and attracts redfish and specks. Read these tips from Gulf Shores Orange Beach Tourism, and buy the appropriate Alabama fishing license before you go.

Where to eat and stay

Enjoy live music, outstanding bay views, and great food at Tacky Jack’s 2, only minutes from the fort. Start with the heavenly, creamy smoked tuna dip served on a lettuce bed with toast points. Then savor the shrimp and grits, drowned in butter. The restaurant seasons and grills gulf shrimp and serves them on cheese grits, topped with Conecuh sausage and house-made Spicy Tacky with some of the best green beans I have ever eaten.

This Northern girl ordered a half-and-half to drink, thinking of an Arnold Palmer, that is half tea and half lemonade. Nope. A Tacky Jack’s half-and-half is half sweet and half unsweet tea.

Roxie’s reliable recommendation: Stop for a selfie with the marlin hanging from a frame outside.

The peninsula has numerous vacation rentals and several RV parks. Fort Morgan RV Park is the closest to the fort.

Continue story below.

Fort Morgan and the Battle of Mobile Bay

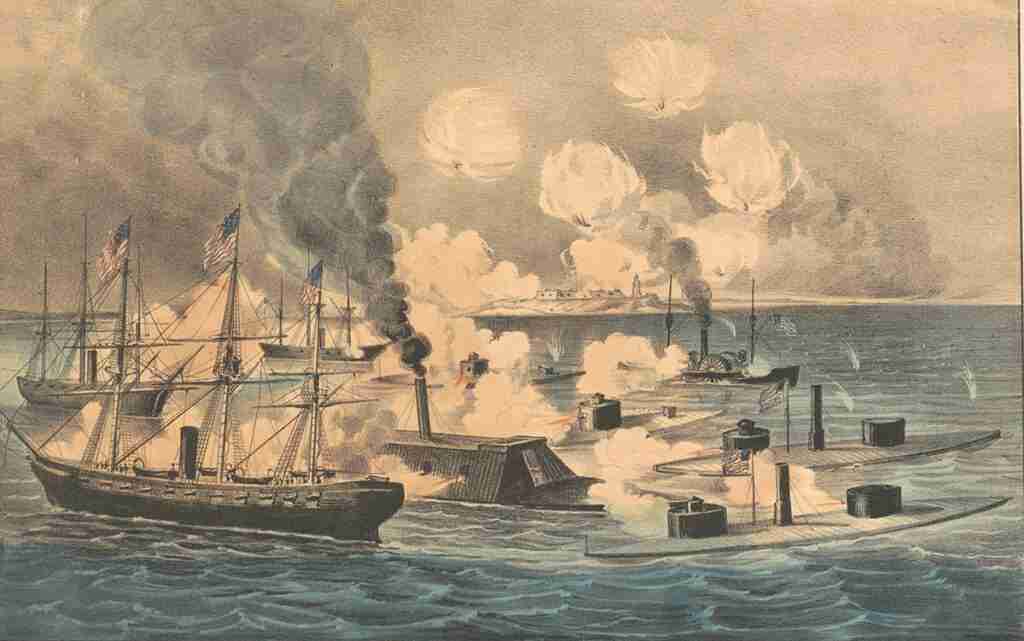

Rear Admiral David Farragut’s ships steamed into the mouth of Mobile Bay on August 5, 1864. The USS Brooklyn led the way with Farragut commanding from the USS Hartford. The fleet had both wooden and iron-plated ships, called monitors. Farragut preferred the wooden ships, but the monitors soon proved their worth. Fort Morgan’s cannons hurt the wooden ships but their shots bounced harmlessly off the monitors.

However, the Union scouts had failed to spot the shipping channel’s torpedo field, what we now call mines. The monitor USS Tecumseh struck a torpedo while pursuing the Confederate ram CSS Tennessee. The Tecumseh sank immediately, drowning 93 sailors and trapping the Union fleet. Farragut told Hartford pilot Martin Freeman to take the lead, and “go in the bay or blow up.” The pilot ordered four bells: “Go ahead at full speed.”

Eventually, Farragut’s orders transformed into a famous quote: “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead.”

The Hartford led the way while the torpedoes banged on the fleet’s hulls. None of them exploded and the fleet escaped artillery range. The Union captured three Confederate gunboats and the Tennessee. Later investigation showed that most of the torpedoes had waterlogged gunpowder. Farragut had won the Battle of Mobile Bay.

The forts surrender

On land, Union General George Granger’s soldiers landed on Dauphin Island, a barrier island across from Fort Morgan. The Union shelled the island’s Fort Gaines until it surrendered on August 8. Then, the Union army besieged Fort Morgan until Confederate General Richard Page surrendered on August 23.

As a result, Mobile Bay was closed to Confederate shipping, further strangling Confederate shipping. Union Admiral Farragut’s victory combined with the Fall of Atlanta to boost Abraham Lincoln to reelection in 1864.

Roxie’s reliable report: Because the Congressional Medal of Honor was then the only American decoration for valor, 97 enlisted sailors, Marines, and landsmen received it, the most of any single engagement in American history.

Mobile falls in April 1865

Even though the Union had won the Siege of Fort Morgan, the Union’s manpower shortage prevented it from taking Mobile because the isolated city wasn’t as important. Mobile did not surrender until April 12, 1865, three days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Union General Ulysses Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

Roxie’s reliable report: The Battle of Mobile Bay Trail extends from the barrier islands to the northern end of Mobile County, Alabama.

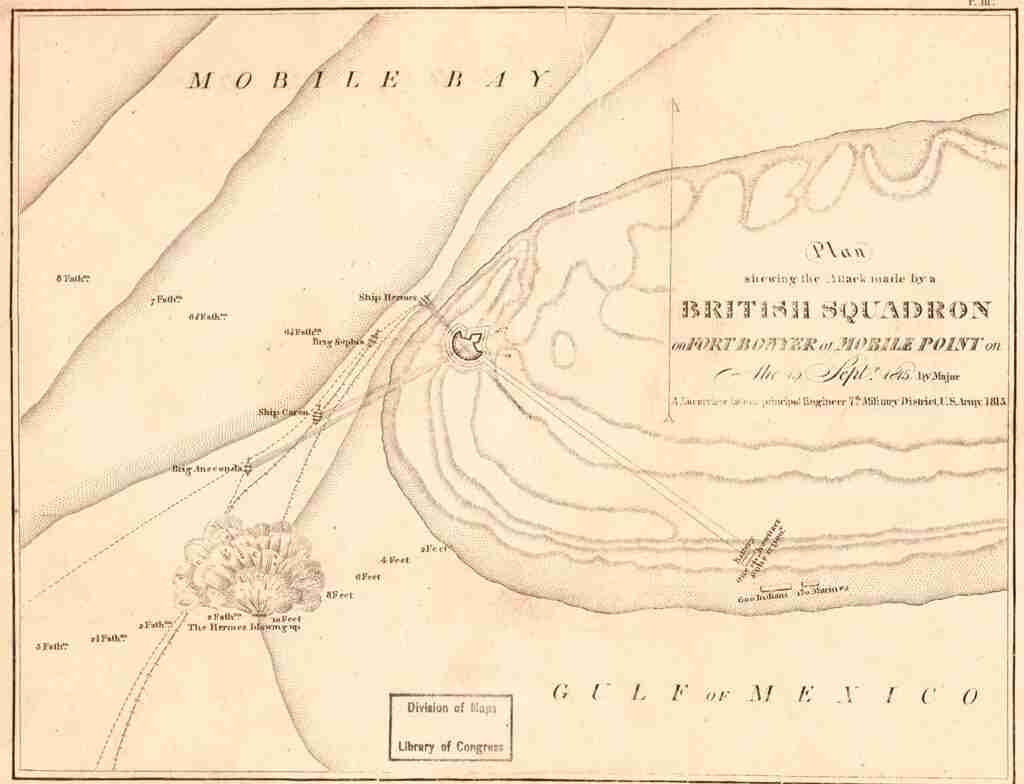

Fort Bowyer, Fort Morgan’s predecessor

The United States seized Mobile from the Spanish in April 1813. Colonel John Bowyer’s soldiers built Fort Bowyer (pronounced BOY-er), a sand fortification, on the eastern tip of the Fort Morgan peninsula. The military abandoned it two months later.

American General Andrew Jackson ordered Major William Lawrence to reopen the fort in August 1814 during the War of 1812’s New Orleans Campaign (PDF). Jackson’s decision was wise because the British attacked the fort twice.

Lawrence’s troops first defeated Royal Navy Captain William Percy’s attack in September 1814. The British hoped to march from Mobile to Natchez, Mississippi, isolating New Orleans from the north. Undeterred, they marched directly on New Orleans, where General Andrew Jackson defeated them.

The War of 1812’s final battle

After their defeat, British warships sailed for Mobile Bay again. A combined force of British Royal Marines and Creek Indians besieged the fort for five days. British General John Lambert forced Lieutenant Colonel William Lawrence to surrender the fort on February 12, 1815.

During the surrender ceremony, Lawrence gave up his sword to Captain Tristram Rickets of HMS Vengeur. Two days later, HMS Brazen brought news that America and Britain had signed a preliminary peace accord. Despite this, Rickets retained Lawrence’s sword, which his family still preserves in England.

In Washington, Secretary of State James Monroe exchanged signed treaty copies with the British Ambassador on February 17. The signatures formally ended the War of 1812 at noon on the next day.

Jackson learned of the ratification in New Orleans on March 13. His message to Lambert about the war’s end arrived on March 15, and soon the British sailed away. Lawrence faced a court-martial in New Orleans on March 25 for his surrender, but the court acquitted him.

At the beginning of the war, the United States hoped to annex Canada. Instead, the Americans only captured the future Baldwin and Mobile counties in Alabama. The Second Battle of Fort Bowyer was the war’s final land battle. Even though the Americans had lost the battle, they retained Mobile Bay.

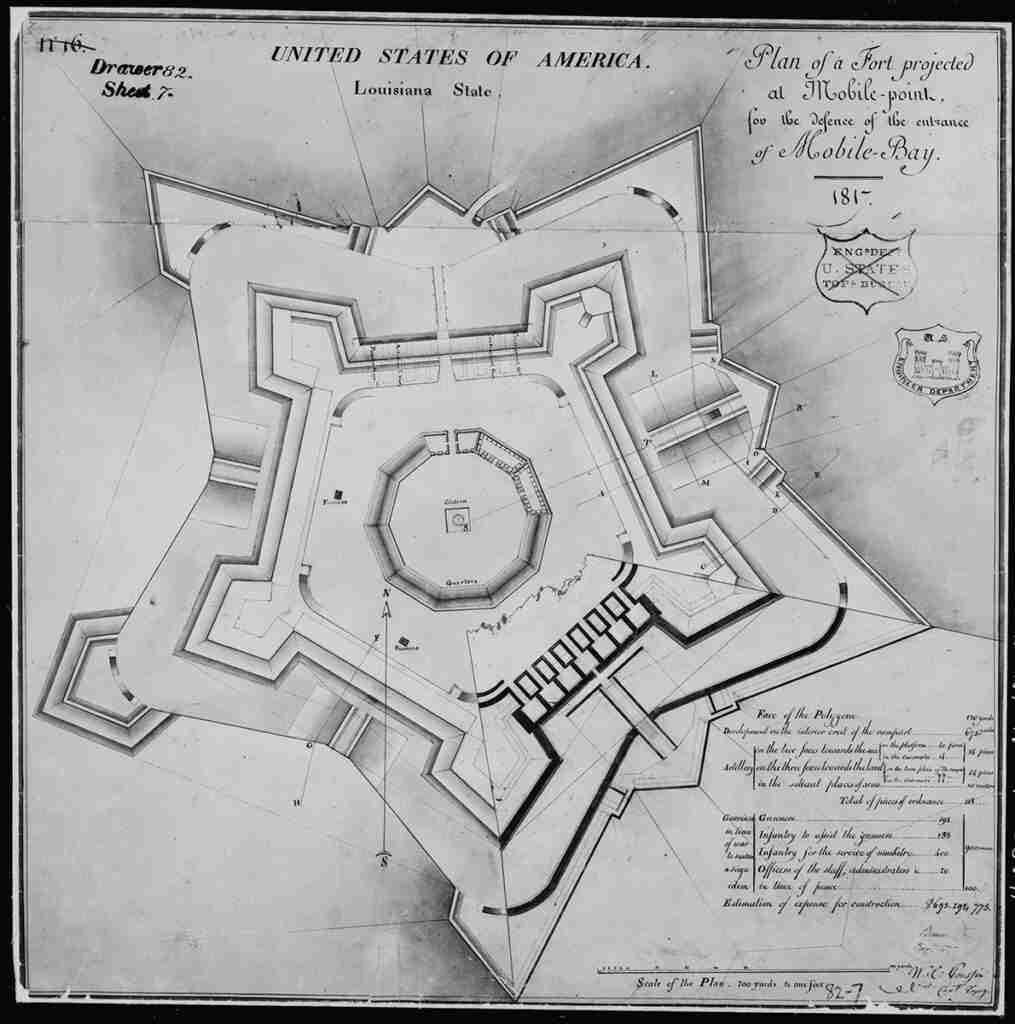

Construction of Fort Morgan

After the War of 1812, Congress authorized the Third System masonry fort type, including two forts on Mobile Bay’s barrier islands in 1819. Fort Morgan, named for Revolutionary War hero Daniel Morgan, would guard the ship channel. Fort Gaines on Dauphin Island, three miles away, would offer sheltered anchorage in Mobile Bay. The brick and stone forts were more resilient than the previous dirt and lumber forts. However, the forts were too far apart to support each other.

Private contractors began building the brick-walled 479-acre Fort Morgan in 1819. It’s named for Revolutionary War General Daniel Morgan, Because of its isolated location, building materials came via ship to the engineers’ wharf north of the fort. Materials included 40 million bricks made by enslaved laborers. Skilled masons, many of them enslaved African Americans, built the fort. Captain Rene DeRussey became the project’s chief engineer in 1825, replacing the private contractors.

The fort was still under construction when Revolutionary War hero Gilbert de Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, left Mobile Point for New Orleans on April 8, 1825. Lafayette was on his American farewell tour.

The Corps of Engineers completed Fort Morgan in 1834.

Captain Francis Belton commanded Company B, Second U.S. Artillery during the fort’s first 18 months. The War Department removed the troops at the end of 1841. Instead, an ordnance sergeant and a caretaker detachment maintained it.

Related: Belton, then a colonel, commanded the Fourth Artillery at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1856.

Confederates seize the fort

Realizing Fort Morgan’s strategic importance, Colonel John B. Todd and four companies of Alabama volunteers seized the massive fort on January 3, 1861, eight days before Alabama seceded. The Alabamians moved the fort’s 18 heaviest guns to face the channel. The volunteers built redoubts and trenches east of the fort to hinder any land attack on Mobile Point.

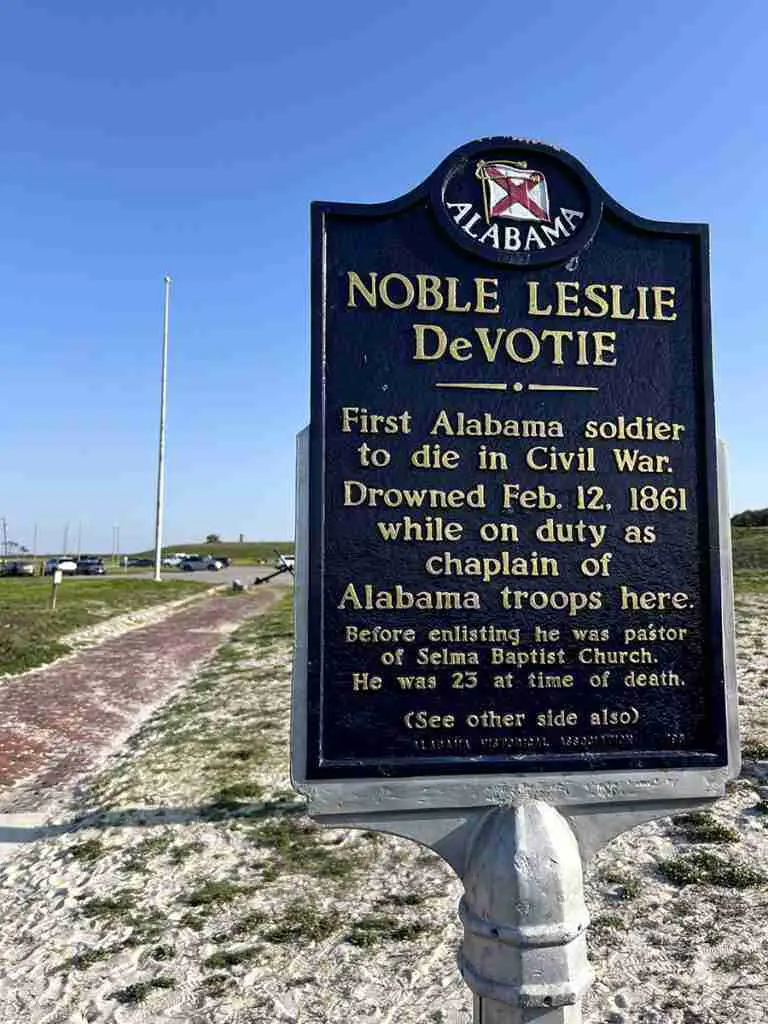

Roxie’s reliable report: Alabama lost its first Civil War casualty when Chaplain Noble Leslie DeVotie drowned at Fort Morgan on February 12, 1861, exactly two months before the war began.

Fort Morgan after the Civil War

The Army installed a series of batteries beginning in 1899. The first one, Battery Bowyer, had artillery that was ineffective against modern naval vessels. Two additional batteries added in 1900 bolstered the fort’s defenses. Battery Duportail’s two 12-inch rifles could fire half-ton projectiles more than eight miles. Their carriages used the guns’ recoil to drop the artillery from sight, so gun crews could reload in greater safety. Battery Dearborn had 12 mortars targeting specific zones with designated charges and projectiles. Two smaller batteries defended the new minefield.

Fort Gaines received two 6-inch disappearing guns.

Related: The Rock Island Arsenal produced many Army munitions.

The forts in the World Wars

Early in the 20th century, the Army destroyed Fort Morgan’s obsolete armaments by stuffing explosives down their muzzles. Ordnance staff hauled the fragments onto ships docked at the engineers’ wharf. Because Fort Gaines was hard to reach, the Army left its guns. The coastal artillery didn’t replace the obsolete guns during World War I, but units used the forts anyway. Both forts were training bases. The Army deactivated the two posts by 1923.

As World War II approached, the US government repurchased the barrier islands’ forts in November 1941 for coastal defense. Army, Navy, and Coast Guard units protected Mobile’s shipbuilding industry, and a coastal artillery unit staffed Fort Morgan’s guns.

The Coast Guard searched for German U-boats in the Gulf of Mexico from Fort Gaines.

The fort becomes a historic site

The Army again deactivated the forts in 1946. The federal government returned most of Fort Morgan to the State of Alabama. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1960, the property operates the Fort Morgan State Historic Site under the Alabama Historical Commission. The Dauphin Island Park and Beach Board owns Fort Gaines.

/

Book your trip

Let’s add your trip to your calendar! Roxie’s reliable recommendations will get you ready.

Insure your trip:

Plan your flight and book your tickets:

- Aviasales

- CheapOAir

- Priority Pass (provides frequent travelers with airport lounge access around the world)

Plan your overnight accommodations anywhere from national chains to private homes with:

Save on activities, from tours to attractions: